Easter Eggs in Public DNS Resolvers

2022-02-23

Free public DNS resolvers are important services, and there's a bunch to learn from them

DNS exists in a weird place in the modern network. It's foundational but underappreciated and regularly blamed for everything that goes wrong.

It's important enough that ISPs generally run their own (usually bad) DNS services. For such an important service, these ISP services don't cut it and so several major companies give away public DNS services for free, notably Cloudflare's 1.1.1.1 and Google's 8.8.8.8 although there are lots more.

Since these public DNS services are pretty well known, they're interesting almost by definition; they're huge services handling a lot of traffic with intense uptime requirements. Let's take a look at them and learn some stuff!

IP Addresses in TLS Certificates

As a marker of identity, IP addresses aren't great: they're difficult to remember, expensive (at least for legacy IPv4 addresses), and they're recycled regularly. That's where DNS comes along: it shields us from IP addresses. That's a huge win; it's easier to remember domain names and being free to change IP addresses behind the scenes gives us a lot of flexibility.

There's a bootstrapping problem with DNS though in that we can't rely on DNS to resolve the address of a DNS server. That's why Cloudflare and Google's public DNS services are colloquially known by their IP addresses - 1.1.1.1 or 8.8.8.8 - and not by their domain names (which they do have!)

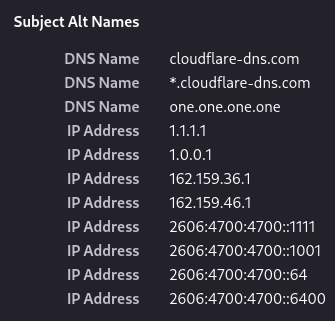

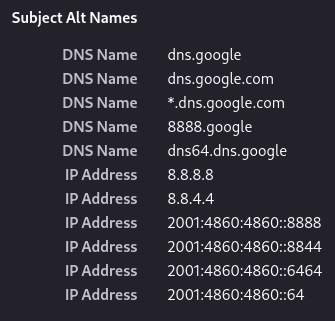

Since IP addresses are generally poor markers of identity, most things online which use TLS have certificates which include a domain name and not an IP address; some issuers will actually refuse to issue certs with IP addresses in them. But Cloudflare and Google are hosting websites on port 443 at the addresses their services are known by, so they do actually need a way to secure them.

So, unlike the vast majority of web services both Google and Cloudflare have TLS certificates which include the IP addresses of their services, as well as various domain names. As a TLS nerd by trade, IP addresses in publicly trusted certificates are a novelty I enjoy finding:

Easter Eggs in Domain Names

We hinted earlier that they there are domains which resolve to those addresses. At the time of writing, Cloudflare's domains lead to an informational site about 1.1.1.1 along with setup instructions, while Google's domains lead to a DNS resolver tool.

I think Cloudflare deserve a special mention here for registering one.one.one.one. You can easily imagine the mistake that leads to somebody typing that; so while it's an Easter egg it does also serve a purpose.

The existence of these domains brings us back to that bootstrapping problem again, though - when configuring DNS resolvers for their machine, a user can't really specify a domain name because they don't have a DNS resolver to resolve it!

Better DNS-over-HTTPS?

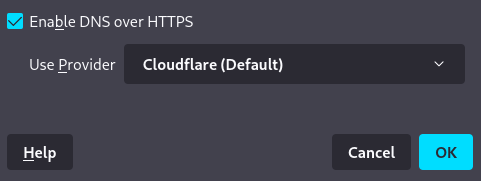

Most techy users will likely be just fine with the concept of using an IP address to configure their DNS resolvers and as such DNS bootstrapping issues aren't really a concern. There is a place where I regularly encounter exactly the bootstrapping problem I described, though: DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) settings:

The actual domain name - in Firefox at least - is viewable in "about:config" under the key "network.trr.uri", which at the time of writing has the value "https://mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com/dns-query" by default. So how does this not cause a bootstrapping issue?

Well, Firefox can work around this just fine, since in practice basically every machine which is running a web browser is going to have working DNS and so Firefox can simply use the host's DNS just to resolve "mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com", and then use DNS-over-HTTPS for all future requests.

The followup question though is... "Why use a domain name at all, though?" We've already established that Cloudflare runs an HTTPS server on https://1.1.1.1 so why couldn't Mozilla have used the IP address directly rather than a domain?

For one thing, mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com isn't 1.1.1.1: at the time of writing, the domain resolves to "104.16.248.249" among other addresses. Those addresses don't host a usable website right now; they give an HTTP 403 error, and only do so over HTTP, not HTTPS. So using, say, "https://104.16.248.249" just won't work because Cloudflare never configured it to work like they did for https://1.1.1.1.

So what if we use "https://1.1.1.1/dns-query" as the DNS-over-HTTPS URI? Well, it works just fine.

In fact, using the IP address in that way is simply better. For end-users, I can't think of a benefit to using a domain here; if your system's usual DNS resolver went down but you were using DNS-over-HTTPS via https://1.1.1.1 you'd never notice anything wrong in Firefox because you wouldn't need the local server at all!

More importantly, the user's configured resolver could be actively malicious and refuse to resolve mozilla.cloudflare-dns.com. An ISP might do this to try and force customers to use its (terrible) DNS servers for tracking purposes. This isn't theoretical; it does happen and you can see a few examples of people complaining about Cloudflare DoH being blocked if you search for it. Of course, the ISP could block all traffic to 1.1.1.1 but at least using a the IP-based DoH URL avoids one potential issue!

Google DNS works the same for DoH; you can use https://8.8.8.8/dns-query and it'll work just great!

To be clear I'm absolutely not attacking Mozilla or Cloudflare for the use of a domain by default. The domain has a couple of upsides for Cloudflare and at the end of the day they're giving away their DoH service for free. It's totally reasonable for them to use this domain as a default.

Still, if you're tech-savvy and use Firefox with DoH, you might as well change to using an IP here and reap the rewards of having improved your DNS setup a little - and benefit from some DNS easter eggs!